A Road Map towards freedom from Lungsickness and FMD for the Northern Communal Areas of Namibia

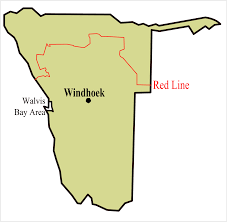

Breaking down the barriers caused by the Red Line – a veterinary cordon fence dividing North from South.

Ausvet had the enormous privilege of working with the Government of the Republic of Namibia in a complex and far-reaching project to help the Directorate of Veterinary Services (DVS) and the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry (MAWF) design and implement a Road Map towards the declaration of the country’s Northern Communal Areas (NCA) Free from Foot and Mouth Disease (FMD) and Contagious Bovine Pleuropneumonia (CBPP or Lungsickness). The southern of the country has been recognised as free from FMD and livestock owners have benefitted from access to the valuable European markets.

In terms of disease status, the NCA was well advanced in meeting the stringent international requirements to achieve FMD-free status having eradicated the disease. However, in terms of other requirements, including movement control to prevent disease incursions, surveillance to demonstrate freedom and surveillance for early detection of outbreaks, there were significant weaknesses that needed to be addressed before making an application for free status. The movement of livestock became the most challenging question.

The livestock owners, their traditions, cultural needs, attitudes and motivations were of primary importance in order to understand the movements of their animals. Huge herds would move across the porous borders with neighbouring countries in search of grazing land because the competition for feed has become so great in the NCA. Sometimes single animals would be brought from deep inside Angola as part of family funeral rituals. Land ownership, families and tribal groups are spread across the region with little heed paid to political borders. Wildlife too, move freely from one country to the next, sometimes predictably, at other times not. The disease and immunity status of livestock and wildlife in neighbouring regions, the capacity of field services and community engagement were also crucial elements which needed to be understood

Namibia is a beautiful country in south western Africa, sharing borders with Angola and Zambia in the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south and east, and independent from South Africa since 1990. The country has enjoyed political stability since gaining independence in 1990 and has undergone strong development in a number of sectors since that time.

Namibia has had a troubled past due to European colonisation then South African rule and its apartheid regime. The Northern Communal Areas in the very north of the country have suffered in a multitude of ways from physical and trans-humance barriers which have restricted the free movement of citizens and livestock for well over a hundred years. These barriers were initially established to limit the transfer of diseases from animal populations between the north and white-held south during the German occupation of South West Africa in the late 1800s in order to contain a major Rinderpest outbreak. During South African rule however they were used to control the movement of native and indigenous Namibians as well as their animals causing untold hardships. The veterinary cordon fence, or ‘Red Line’ as it became known, exists to this day as a reminder of these years of oppressive rule, discrimination and deprivation. It still divides north from south, black from white, poor from rich, overgrazed to underexploited and perpetuates the political divides from which the independence movement and the current day government itself were born.

Northern Namibians are largely indigenous people from several different tribal groups found across the countries of the region. Most practice a traditional way of life, speak only local languages, have distinct cultural practices and follow traditional livestock husbandry methods. Livestock production is socially and economically important and largely focuses on cattle but small ruminants (e.g. goats and sheep) are also important. The shared communal grazing lands of the north are used to feed their animals. The population of the NCA has grown and so too has the animal population which has doubled in the last 20 years leading to overgrazing, irreversible land degradation and a range of associated problems.

The Government of Namibia is committed to removing the Red Line but are faced with a complex dilemma. Before the Red Line can be removed, an FMD-free status needs to be established and the eradication of Lungsickness achieved for the NCA because over its lifetime the fence has affected the distribution of livestock diseases across the country. It currently marks the limit of the FMD-free zone enjoyed by the southern graziers. It also effectively relegates the Northern Communal Areas to act as a buffer zone to protect the south from disease incursions entering through the porous border with Angola and protect the FMD-free status of the south. This hard-won and jealously guarded FMD-free status allows Namibia access to valuable meat export markets in Europe.

With Funding from the Millennium Challenge Fund, the Namibian Government contracted Ausvet to develop a roadmap or clear pathway which would help them collect the necessary evidence to prove freedom from FMD and to take the steps necessary to eradicate lungsickness from the NCA.

Ausvet worked closely with colleagues from MAWF and DVS for many months engaging the diverse communities in the NCA and further south in widespread consultations in order to first understand the challenges but then to harness consensus towards an agreed plan of action. The process used in developing the plans was an interesting one and it extended well beyond the range of epidemiological questions we usually have to consider. Any roadmap had to include a careful understanding of cultural values and traditions as well as animal husbandry practices, the social drivers of disease and other factors influencing risk. Some of these included market opportunities available to NCA farmers, the availability of grazing land and water, land degradation, rotational grazing practices, slaughter practices, disease reporting, veterinary services, community animal health worker networks, treatment and vaccination programs and donkey populations.

As a result of a great deal of thought and hard work, a comprehensive plan was formulated and presented to Parliament for approval allowing MAWF and DVS to put into place programs for improving community engagement in disease surveillance, supporting veterinary field services, developing strategies to meet the traditional and cultural needs of livestock owners, strengthening surveillance at border posts and operating procedures for dealing with incursions of disease.

The “roadmap to freedom” was the result of broad collaboration by many stakeholders’ with a dedicated and optimistic team of specialists and was one of our most enriching projects to date.